An important event happened this week that I hope will be one more step along the path toward de-bunking the idea that economics is solely the study of greed and money and selfish profit-seeking behavior. Too often students (and non-students including some of my social science colleagues!) get this impression and are turned off by the subject, perhaps because of the way we teach our introductory classes with an over-emphasis on traditional interpretations of price-based competitive markets and also because most of the time when an economist is quoted or interviewed in the news they are being asked about events on Wall Street or actions of the Federal Reserve.

An important event happened this week that I hope will be one more step along the path toward de-bunking the idea that economics is solely the study of greed and money and selfish profit-seeking behavior. Too often students (and non-students including some of my social science colleagues!) get this impression and are turned off by the subject, perhaps because of the way we teach our introductory classes with an over-emphasis on traditional interpretations of price-based competitive markets and also because most of the time when an economist is quoted or interviewed in the news they are being asked about events on Wall Street or actions of the Federal Reserve. The truth is that we do talk a lot about money in economics, although for most economists that is simply a shorthand unit of measurement that we use for convenience. We could do most of our analysis by considering any unit of measurement that relates to optimizing decision behavior -whether that is time, happiness, health, knowledge, equity (or yes, sometimes money).

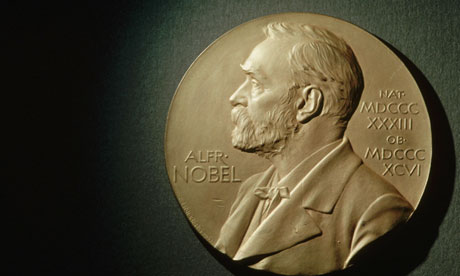

The Nobel prize was awarded to Alvin Roth and Lloyd Shapley this week for their contributions in studying optimal allocations in "markets" that are not governed by prices. The standard workhorse economic model of supply and demand and market-based exchange is generally thought of as an efficient mechanism for allocating scarce resources by essentially matching buyers and sellers according to their price bids (either the asking price of sellers or the offering price from buyers). However, the situations Roth and Shapley looked at were exchanges in which prices were not the relevant allocation mechanism or the relevant metric for efficiency.

They looked at efficient allocation of students into admissions slots in colleges (as a college, you're [hopefully] not interested in auctioning off slots to the highest bidders - you're interested in building a diverse student body made up of the best and brightest students). They looked at markets for matching preferences of medical students and needs of residency hospitals - in a case like this, you can't always get your most preferred posting, but that doesn't mean you can't design a system to give people the best possible match). They looked at mechanisms for matching kidney donors and transplant patients, models of school choice to allocate public school students into elementary and high schools. All of this occurs without any money changing hands, yet efficient operation of matching in these exchanges is as (or more) important than efficiently operating "traditional" price-based markets.

If you look at the trajectory of important economic research and advances over the last 30 or 40 years, much of it has come in exploring situations that have little to do with prices. We have all been conditioned at this point to think of a free market as the most efficient way to allocate something like t-shirts or pairs of shoes by matching those who most value wearing them with those who can produce them in the most cost-efficient way (although even here markets may lead to bad outcomes from the possibility of slave or child labor in production or non-sustainable practices in cotton agriculture, etc). The first month and a half of my introductory econ classes are largely devoted to explaining how free markets work and understanding their potential benefits to the market participants. However, increasingly economists are exploring the limits of these models and better understanding the effects of strategy, uncertainty, and external spillover effects in exchange and we are more carefully considering the importance of human and social capital in exchange and optimal behavior. To me, as an economist who has little interest in banking, finance, or money, per se, but lots of interest in human behavior, strategy, and policy making, this is an exciting time for my profession and gives me hope that we can continue to really make positive contributions to the understanding of human behavior.

On a related note, one of my students is starting on a project exploring the question of markets for open-source material. This is a fascinating area in our new digital economy because so much of what we value now has an entirely different cost and pricing structure. We can replicate digital copies of things at zero cost ... imagine if Henry Ford could have hit Control-C on his keyboard and made a duplicate Model-T just that easily? That's the world we're living in today for information, art, music, games, literature ... etc. Gutenberg's printing press profoundly changed the production of the written word and lowered costs considerably, but it is a fundamentally different mathematical problem than digital reproduction. That innovation took us from a world where it took maybe 15 minutes of labor to copy a page of text to a world where it took a few seconds of labor and the help of a machine. We're now in a world where it literally has ZERO cost - you could write a computer code to continue replicating files and it could proceed to do so forever like some type of perpetual motion machine. As anyone who's ever tried to divide a number by zero on their calculator knows, when you put a zero in a math equation, lots of things have the potential to blow up. How do we price things and make decisions about production levels when we can essentially wave a magic wand and have as much of something as we want?

Phenomena of open-source and "crowd-sourced" material like Wikipedia are also fascinating economic questions ... why does anyone put in real time and effort to contribute to something that will be anonymous and they will receive no tangible benefit from? The answers must have to do with social reputations, collaboration, community, or personal satisfaction from the creative process. Very little of this is in the Adam Smith-type bartering model of economic behavior and so these new situations where things are literally given away for free and our most important time and labor output is in the form of information not tangible manufacturing goods provide some really exciting opportunities to ask new and important economic questions.

These are the questions that modern economics has to address to continue to explain behavior, exchange markets, and decisions of individuals in today's economy. Economics in general spent too many years ignoring what our colleagues in other disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, and psychology were learning about human motivations and now that we are finally starting to value those great contributions and incorporate them into our understanding, I think we're seeing great strides being made as a result. Kudos to the Nobel committee for continuing to recognize some of these contributions that push the boundaries of economic knowlege.

So it's economists who perpetuate the use of the word "kudos"? Hm. Ironic that it came in the same sentence as "pushing boundaries".

ReplyDeleteSeriously though- I agree. I think economists can offer a way to rephrase (at the very least) or better understand (at best) the stuff other disciplines have been obsessing over for a long time. It seems like there is movement from even cultural anthropologists (the group I would ordinarily think of as the most antithetical to economics) to exchange topics/language with economists today for these reasons (either to make their work sound more relevant to more powerful audiences or to actually seek out the unique insight from economists that explain more fully the stuff they've been studying for a while). It's nice to hear economists are game for that exchange too. Of course, we've been seeing that in our department for a while now. Because we're that awesome. :)